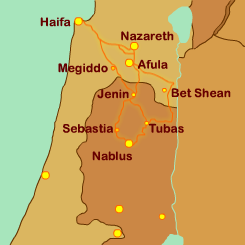

My friend Loren and I left the University at about one o’clock and made our way to Afula, then to Bet Shean by 4:00.

Our first ride was with a dati (religious) family who had absolutely no room and were going just a short distance—yet

they stopped for us and squeezed in order to help us out. Our second hitch was with a family of West Bank moshavniks.

The father was an immigrant, a very nice man, the children completely Israeli. We were worried the Israeli soldiers

would not let us cross the border into the West Bank, so when the father stopped and asked them directions I held my breath.

But we soon learned that the army gives no problems to travelers. We also learned that the Palestinians are beautiful people.

The father was an immigrant, a very nice man, the children completely Israeli. We were worried the Israeli soldiers

would not let us cross the border into the West Bank, so when the father stopped and asked them directions I held my breath.

But we soon learned that the army gives no problems to travelers. We also learned that the Palestinians are beautiful people.

He dropped us off and we walked to what was marked on the map as a hot spring with a hostel. It turned out the hostel had

been abandoned and was now inhabited by a Palestinian family. They invited us in—and wouldn’t let us go! First they fed us,

then we talked for a long time, then they fed us again. I felt so happy spending the evening with this family. They clearly

love each other and have such fun playing together. We sang, danced, looked through their Hebrew-Arabic book together.

Then we slept there. The family consists of the grandfather, Ali, the mother, Naja, and her five daughters: Miriam, Fatma, Hitam, Tamam, Hiyam.

They were poor people but they shared what they had with us. I was moved when they wanted to give us a special dessert. They opened

a jar of jam, and we ate it by spoonfuls. Here was a family with almost nothing opening their special jar of jam for us.

a jar of jam, and we ate it by spoonfuls. Here was a family with almost nothing opening their special jar of jam for us.

I was traveling with my buddy Loren, and this caused some cross-cultural confusion. The family assumed we must be married and

so they gave us a room by ourselves, laid out two mats for us to put our sleeping bags on, and pushed them together.

I told them, “La mujawizzin, la mujawizzin,” ("Not married!") and separated the mats. They seemed confused and a little upset by this, so in the

end I think I just said, “Mujawizzin,” ("Married") and let them push the mats together. This seemed to make them feel much more comfortable,

and they smiled. After the girls left, we pushed the mats apart again.

The girls were goatherdesses, and the next morning we awoke very early to a wonderful breakfast: fresh, warm goats’ milk.

They had heated it so it steamed just a little and it was delicious and sweet.

The girls were goatherdesses, and the next morning we awoke very early to a wonderful breakfast: fresh, warm goats’ milk.

They had heated it so it steamed just a little and it was delicious and sweet.

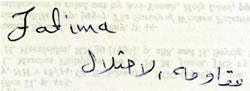

We hitched to Tubas, and from there took a taxi to Nablus. The Old City of Nablus has a nice shuk. We met a young woman named

Fatima, and she invited us back to her house.

She was eager to tell us about the political injustices she experienced at the

hands of the Israeli authorities. She showed us her identification card she is required to carry and the receipt for a fine

she had to pay for being involved in a demonstration. She seemed a bit evasive about the details, or did I just perceive

that because it was hard for me to hear these things? She said she had been fined some thousands of shekels because of something she

could not explain in English. So she wrote it down in Arabic for me. An Israeli friend later translated her note for me:

She was eager to tell us about the political injustices she experienced at the

hands of the Israeli authorities. She showed us her identification card she is required to carry and the receipt for a fine

she had to pay for being involved in a demonstration. She seemed a bit evasive about the details, or did I just perceive

that because it was hard for me to hear these things? She said she had been fined some thousands of shekels because of something she

could not explain in English. So she wrote it down in Arabic for me. An Israeli friend later translated her note for me:

התנגדות לכבוש

— "opposition to the occupation."

התנגדות לכבוש

— "opposition to the occupation."

After leaving Fatima we walked through town and enjoyed beautiful chanting of the Qur’an. Perhaps this was the memorial service

for a beloved relative? I recall stumbling upon such memorials several times, often in large tents created by stringing

quilts across an alley. Gorgeous singing, steaming Turkish coffee.

We went to An-Najah University and talked with a number of students. They often greeted us by saying, "Welcome to Palestine." Again, they quickly told us stories about harassment by the

Israeli authorities, showing us a number of flyers in Arabic. The flyers documented repeated harassment in the form of roadblocks and deportation of faculty who refused to sign

a document denouncing the PLO.

We took the bus back to the center of town and ate knafa in the Old City.

We took the bus back to the center of town and ate knafa in the Old City.

After our dessert we tried to find the Samaritan section of town. We located the Samaritan Quarter—but everyone had moved.

Then we met a group of really nice high school boys who escorted us to the Samaritans’ new neighborhood and their synagogue.

But everything was closed, because of the Sabbath, we thought. So the boys led us back to the city center, insisting on buying

us cokes along the way. Then they insisted on paying for our taxi to Balata!

At Balata we went down to Jacob’s well, which was beautiful. We lowered the bucket—that woman must have been strong.

We met some soldiers who explained how to hike up Mt. Gerizim, so we caught a bus to the Bracha intersection and began walking up.

After an hour and a quarter we reached the Samaritan village. An Israeli we met along the way told us to ask for Yosef Cohen,

that he would delight in telling us about the Samaritans—we asked and he did.

We entered a tent and found a group of Samaritans who welcomed us warmly.

We talked for awhile, learning about the differences

between the Samaritan and Jewish religions. A respectful interfaith dialogue between a Christian (me), a Jew (Loren) and

some Samaritans. They told us about the different pronunciation of their Hebrew, and about the five pillars of the Samaritan

faith: One God, Moses the Prophet, Torah, Har Gerizim as holy place, heaven and hell. We asked if they had a high priest.

They said yes, and what is more, he lived right nearby. So we went to visit him.

We talked for awhile, learning about the differences

between the Samaritan and Jewish religions. A respectful interfaith dialogue between a Christian (me), a Jew (Loren) and

some Samaritans. They told us about the different pronunciation of their Hebrew, and about the five pillars of the Samaritan

faith: One God, Moses the Prophet, Torah, Har Gerizim as holy place, heaven and hell. We asked if they had a high priest.

They said yes, and what is more, he lived right nearby. So we went to visit him.

The members of the Samaritan priestly family wear payyus, unlike the laymen. The high priest traces his lineage all the

way back to Aaron. He showed us their Torah. It has an intricate, ancient-looking script—exotic and gorgeous. We walked

back to the tent, and then down to synagogue service, from 5:30-6:30.

On our way to the service we saw a young man out in the bushes. He had wild, unkempt hair, and his clothes looked like

something John the Baptist would have worn. He had what looked like home-made tefillin wrapped across his forehead, with a brown box hanging in the middle.

He also had a bulky, worn leather pouch around his neck. We did not get

a chance to speak with him, but I was intrigued. It felt like we had stumbled upon a prophet from the Bible.

After the service, we went back with a Samaritan named Uzzi to his house where we talked, ate mazzah and bananas, and

leafed through the “A.B. News.” His father is named

רגא אלטיף

Raja Altif. He gave me his address in

שכונת השומרונים

(Neighborhood of the Samaritans), which I wrote down in Hebrew.

When we left Uzzi’s house we encountered the prophetic man again and called to him. He replied to us in English, said his name was Mati.

For all his wild appearance, Mati was easy to talk to. Turns out he was from New York, Conservative Jewish upbringing. One evening

Mati looked up at the sky and noticed that Rosh HaShanah was not being celebrated on the Rosh Hodesh. Mati became deeply troubled. He knew something was very wrong.

So he got up—and left. His wanderings took him to Israel, where he decided to take a Nazirite vow. He has not cut his hair since.

His vow will be fulfilled when the Mikdash (Temple) is rebuilt, and he can finally cut off his curls and burn them on the alter of incense.

When we left Uzzi’s house we encountered the prophetic man again and called to him. He replied to us in English, said his name was Mati.

For all his wild appearance, Mati was easy to talk to. Turns out he was from New York, Conservative Jewish upbringing. One evening

Mati looked up at the sky and noticed that Rosh HaShanah was not being celebrated on the Rosh Hodesh. Mati became deeply troubled. He knew something was very wrong.

So he got up—and left. His wanderings took him to Israel, where he decided to take a Nazirite vow. He has not cut his hair since.

His vow will be fulfilled when the Mikdash (Temple) is rebuilt, and he can finally cut off his curls and burn them on the alter of incense.

Mati wears totafot at all times, and the pouch around his neck holds a copy of the Torah. “My goal in life is to live Torah,” he told me.

He has a friendly relationship with God, he said. Mati was attracted to the Samaritans because they have two things essential for following Torah.

They have a high priest, and they have a sacrifice. I was attracted to Mati’s single-minded devotion to these ancient codes.

Something in me wants to be like Mati, or St. Francis, renouncing everything for love of God.

The Samaritans accept Mati and seem to appreciate his respect for their rite. They do have a disagreement with him about his dress

and the wearing of totafot, and Mati said he may be persuaded to change. But he also hopes to teach them and open their eyes to

parts of the Torah they may have neglected.

That night we slept in the Samaritan tent.

Mati

Mati is God's friend. You can see it in his intense stare and his sweeping movements. You can see it in his grubby, pale skin, unwashed for several years, and in his long, ragged brown hair. When they rebuild the temple in Jerusalem, Mati will end his Nazirite vow by shaving off his locks and burning them on the altar of incense.

Because Mati is God's friend he tries to wrap himself up in God. Leather circles wind up his arm to his heart; straps wrap around his brain, holding God in. He never removes those straps – like Jacob, he will not let God escape. One night on Long Island, some years back, staring at the black sky and new Moon, Mati suddenly felt sick. He knew the commandment: that the new year must be welcomed with the new Moon; yet he saw that the rabbis had delayed the celebration until the following evening. His body shook as Mati realized the rabbis had delayed the day, betrayed the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

Mati has not bathed since that night. He sleeps on holy grass under the black sky of the promised land; during the day he argues with Samaritans on Mount Gerizim, trying to persuade them to wrap up in the leather straps he loves.

If you ask him what his goal in life is, he probably will answer, "To live Torah." That is why he always carries the sacred words in a pouch on his chest.

God is Mati's friend. I know he smiles on Mati from the black sky with a crescent moon, as Mati dreams in the holy grass of Mount Gerizim. And Mati smiles in his dreams, as clouds of incense and blood and burning hair bellow from his brain, scorching the straps that hold God in, pouring, pouring from his heart, rising to his friend.

The next day I asked the Samaritans why they don’t wear totafot. They told me there are 140 commands, 70 of which we my keep now.

It is not proper to wear totafot now because there is no Temple. I asked Uzzi, “Why don’t you rebuild the Temple?” Too much money, he said.

We had breakfast with the female members of the family, really nice women. Loren undoubtedly created this opportunity.

Then we walked up to the top of Har Gerizim. We saw the Akeda stone, where Abraham offered up his son. We saw the Drinking Rock.

There is a Byzantine church built over the ancient alter. We walked around the ruins of the Temple, then sat down on some rocks

and looked across the Valley of Schem to Har Ebal. We read Deuteronomy 27 and 28:

אלה יעמדו לברך את העם, על הר גרזים

“These shall stand on Mt. Gerizim to bless the people….”

Then we walked up to the top of Har Gerizim. We saw the Akeda stone, where Abraham offered up his son. We saw the Drinking Rock.

There is a Byzantine church built over the ancient alter. We walked around the ruins of the Temple, then sat down on some rocks

and looked across the Valley of Schem to Har Ebal. We read Deuteronomy 27 and 28:

אלה יעמדו לברך את העם, על הר גרזים

“These shall stand on Mt. Gerizim to bless the people….”

We hiked back down to the city. Then we got a hitch to Sebastia, and spent an hour or two walking around exploring the town and ruins.

From Sebastia we got a number of interesting hitches through the beautiful, hilly countryside of the West Bank.

We went through Jenin and Megiddo, and finally made it back home.

Once again, I managed to pack a lot into my days in Israel. I had to get back to Haifa by 6:00 pm to meet with Elias.

I had loaned his brother, Dahood, a Christian music cassette, and I was frustrated because he never seemed to get around to copying it and returning it.

I told him, somewhat guiltily, that I really needed it back—now—and later asked Elias, "Don't you think I should have asked for it back?"

אתה צודק! אתה צודק!

“You’re correct, you’re correct,” he assured me. (Literally, "You're righteous.") I wonder what St. Francis would say.